SALINAS

Our salinas are located along the hundreds of kilometres of coasts bathed by Mediterranean waters. A name that comes from the Latin “Medi Terraneum” and means sea “in the middle of lands”. This term perfectly describes its situation between the continents of Europe, Africa and Asia and its merger with the Atlantic Ocean in its western side.

Cradle of great civilizations, our ancestors knew how to take advantage of these resources, thus discovering salt as a preservative. It also meant that salt became a highly marketable commodity, affecting the economies of many countries. All of this was undoubtedly fundamental to the progress of the human race.

For this reason, the inhabitants of the Mediterranean basin began to develop salinas in their marshes and to exploit them in an intensive way. These methods remained intact until the twentieth century, when the appearance of other conservation methods reduced the use of salt. Salt obtaining operations were then proportionally reduced, leaving many salinas abandoned or destined for industrial exploitation. Today, approximately 160 salinas are recognizable in the entire Mediterranean.

The 90 still active salt flats produce around 7 million tons of salt, whereas the rest are inactive or transformed. 75% of these salinas are located in the north of the Mediterranean, although the most ideal conditions are in the south. France, Italy, Spain and Greece are the largest salt producers.

Despite the fact that the development of salinas involves a change in the landscape, its resulting environmental impact is low or even positive. This activity is based on the natural dynamics of pre-existing wetlands, on tidal cycles and in the seasonal processes of flooding-desiccation. Therefore, salinas are an example of sustainable exploitation of a natural resource while constituting ecosystems of great richness.

Environmentalists defend these spaces, not only for their landscape and wetland values, but also for making part of the Mediterranean cultural heritage. Thus, many of the abandoned salinas are being restored thanks to scientists, government institutions and owners. Their work mainly consist in promoting sustainable development of the salt flats combining production with tourism.

SOCIAL, ECONOMICAL AND CULTURAL IMPORTANCE

Salt has led to a territorial management that has generated values of landscape, social, environmental or economic types.

The importance of the Mediterranean salinas was more evident in the past, when salt played a very important role in preserving food. Thus it provided power to those who controlled its production and trade. Today salt is still present in monthly payments in some languages (salarium, salary).

Mediterranean salt workers developed a variety of devices and means adapted to the particularities of the land and climate variations. All of this shaped the Mediterranean salina’s landscape, with unique architectural and technical results.

This lifestyle has accompanied the Mediterranean people for more than 2000 years. As a result, it has clearly influenced the behaviour of its people, customs, gastronomy, religion, mythology, legends and superstition.

CURRENT SITUATION

The Mediterranean salinas today face many pressures and threats due to the change of social values and economic tensions. In addition to abandonment, many of these areas serve now for other uses such as ports and airports, or aquaculture. Other salinas have become industrial or part of urban zones. This usually makes the salina’s conditions in the physical environment disappear completely, preventing the subsequent regeneration of the habitat. One of the current challenges is the climate change, which threatens to flood the coastal salt flats.

Fortunately, but only in a few cases, social and economic changes are promoting new perspectives and demands related to public and tourist use. This is opening new ways for their enhancement that will reinforce the economic interest of the environment of salinas.

ECOSYSTEM

The Mediterranean salinas offer a clear example of how the presence and activity of living beings influence their good performance in general. Moreover, it affects the initial crystallization and final texture of the different precipitated fractions. For example, the Microcoleus seaweed mats constitute a relatively impermeable screen that protects the ponds from a partial loss of their brines. This is achieved by infiltration into the clay substrate and facilitate better absorption of sunlight in brine, with the consequent rise in temperature. The Dunaliella salina facilitates enormous energy absorption that significantly raises their temperature and, ultimately, favors evaporation.

In addition, the fauna community that inhabits the salinas, especially the aquatic birds, contribute with their excrement to enrich the brines. This contribution is essential for the metabolism of the numerous photosynthetic organism in the salina environment. Furthermore, it constitutes the main basis of the nutritional system.

BIODIVERSITY

Apart from their historical, cultural and aesthetic value, the Mediterranean salinas are one of the most biologically productive ecosystems on the planet. In general, and due to increasing concentrations of salt, species richness decreases rapidly as soon as the salinity of seawater is exceeded. Therefore, the degree of salinity is the factor that determines the development of specific flora and fauna.

The Mediterranean salinas are wetlands of great ecological interest and great importance for the conservation of biodiversity. Its location makes it the passageway for thousands of aquatic birds during their migratory flights. These flows take place from nesting sites (central and northern Europe) to wintering areas (central and southern Africa).

VEGETATION

There are many plants capable of living in saline environments. Such plants, named halophytes, have developed different mechanisms that allow them to survive in these hostile environments.

What is more, most of these species are unable to thrive in other environments. Some examples are Tamarix, Atriplex, Spartina, Armeria and Salicornia, increasingly known in the gastronomic world. One of the most forgotten species in the salina’s environment is the aquatic vegetation. There are three major taxonomic groups: green Algae such as Dunaliella salina, liverworts and Phanerogamic plants. Some of them interfers with the quality of salt produced.

AQUATIC FAUNA

Along with the entrance of the sea water, other species are also captured. They are mainly mullets, but also soles, seabass and gilt-head sea bream that serve as food especially for aquatic birds.

The macroinvertebrate and ichthyological community is distributed along the salinity gradient, but inversely related to concentration. Indeed, fish, mollusks and annelids, not very tolerant of salinity, remain in the ponds of lower concentration. At the other extreme, the perfect adaptation to highly concentrated brines constitutes an ecological advantage for Artemia salina. This concentration allows to avoid the predation of the first ponds by aquatic birds and fish. After the international salt crisis in the 1970s, many salt flats became aquaculture areas for fish farming.

As the circulation of water does not stop, salinas attract a wide variety of waterbirds which feed on fish and invertebrates that penetrate them. The waterfowl community is usually very rich and diverse as the salinity gradient generates a multitude of habitats for several species. These aquatic birds have morpho-physiological adaptations that allow the maintenance of optimal conditions, expelling the excess of salt.

Thus, avocets, shorebirds, herons, ducks, flamingos, waders, grebes and terns are the most important groups. Gulls and cormorants use the salinas mainly as a day or night base. Some species, such as black-headed or yellow-legged gulls, feed and nest on their dikes and islets.

ARTISANAL SALT

Salt may have marine origin, when it comes from coastal areas and sunny regions, or geological origin. In this last case, the salt is dissolved in water from natural springs which has gone through some saline seam that glently dissolves and brings in suspension a sufficient concentration of salt in order to concentrate and extract it. Finally, the exploitation of salt mines consists in salt deposits in the subsoil and from which some seams allow, through refining processes. However, most of this salt is allocated towards industrial use.

Salt is a product that is well present both in human food and domestic medicine, in remedies applied to people and animals. Artisanal salinas based on solar evaporation work produces the highest quality salt. However, when everything is industrial, the artisanal that persists becomes something valuable.

Fortunately, around the Mediterranean there are still some artisanal salinas and today their products are appreciate in gourmet spaces, such as Fleur de Sel.

SALT EXTRACTION PROCESS

Since ancient times, the inhabitants of the Mediterranean knew that seawater contains salts that are very different in composition and properties. Evaporating water in a single pond would imply the joint precipitation of all the salts present. They also knew that the precipitation of salts from seawater occurs in a fractional way: first carbonates, then gypsum and later halite or common salt.

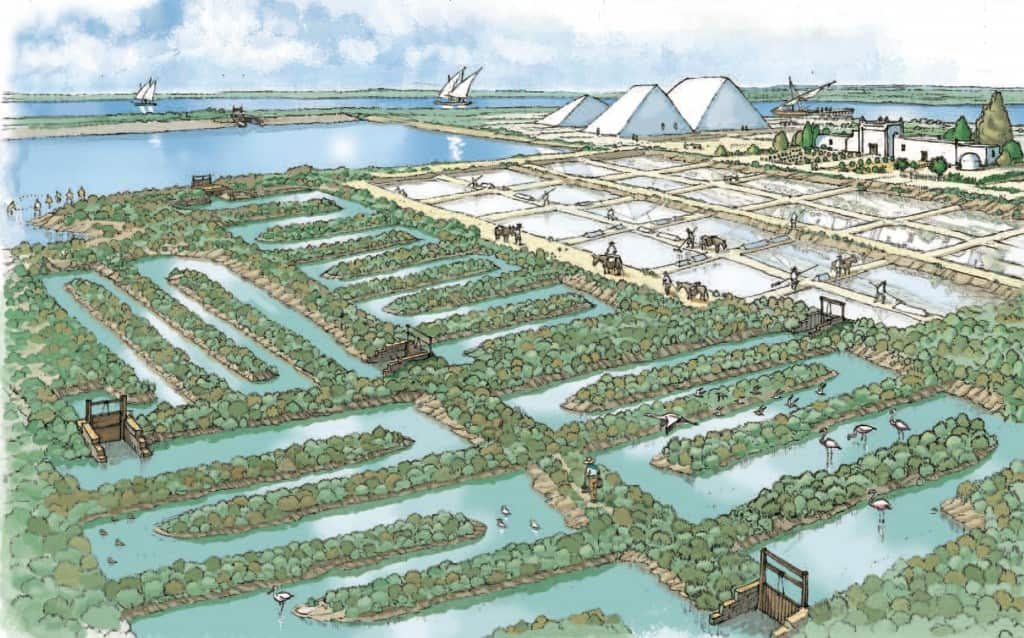

This made necessary the compartmentalization of salinas in several ponds for each part of the process, before obtaining common salt. For this reason, the Mediterranean salina is a system of ponds separated by dykes, in order not to mix water of different concentrations.

In the first place, estuaries store the seawater, extensive lagoons where the salt concentration is 3,5ºBé (36 gr of salt per liter of water). From here, the concentrators receive the pumped water pumped, a labyrinth-shaped structure where water progressively reaches higher levels of salt concentration up to 25ºBé (325 gr of salt).

The resultant water nourishes the last part of the circuit, the crystallizers, smaller ponds where the sea salt crystallizes. There, the graduation reaches a maximum of 30ºBé (370 gr of salt).

It is very important to avoid that concentration exceeds 30ºBé, since in that case magnesium salts begin to precipitate and above 34ºBé, does potassium salts, which give the final product a bitter taste. At this point, salt workers open the gates to let escape any water that may still remain and collect the resulting salt.

The salt obtaining process starts in the months of February-March, when the meteorological conditions begin to be optimal for the evaporation of seawater. Production remains active until September or October, a period in which, as the temperature drops, the process becomes less profitable. Until the beginning of a new season, the ponds are kept full of water and maintenance and repair work on the facilities will be carried out.

The operation of a salina. Source: Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Junta de Andalucía, 2009. (C) Arturo Artefacto.

THE SALT WORKER

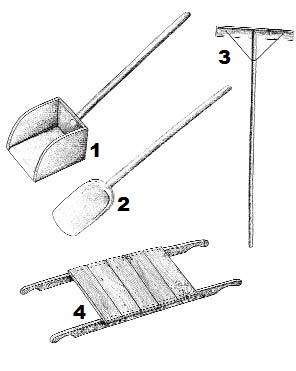

Tools of the traditional salt flats: shovels (1 and 2), rod to extract salt (3), and stretcher (4) to transport it. Source: Salinas de Andalucía, 2004: 91

Working in a traditional salina may seem automatic and simple, but the salt worker not only works controlling the approximate concentration of the water and proceeding, in each phase, to its displacement and subsequent continuous movement of the water in the crystallizers.

Previously, the salt worker prepares the salt flats by fixing the exterior and interior walls, making sure that the floors of the ponds are in perfect conditions and replacing those deteriorated woods that are part of the structures of gates, wells and waterwheels.

During the course of the season, they are exposed to health problems derived from a humid area where high temperatures and long hours of sunshine ensures a high risk of lipothymias. In addition, it is common to suffer skin burns derived from continuous exposure to waters with high saline concentrations or eye burns due to the mirror effect of the sun’s rays on the salt. Furthermore, they usually present muscular and articular problems associated with the load, dragging and repetitive movements.

For generations, salt workers have built, cared for and lived by and for the salt flats. Above all, they have proudly transmitted the “know-how” of their ancestors to maintain and conserve one of the most unusual landscapes in the world and produce one of the best salts. Today, the recovery of artisanal production in certain territories of the Mediterranean has made it possible to preserve this ancient trade.